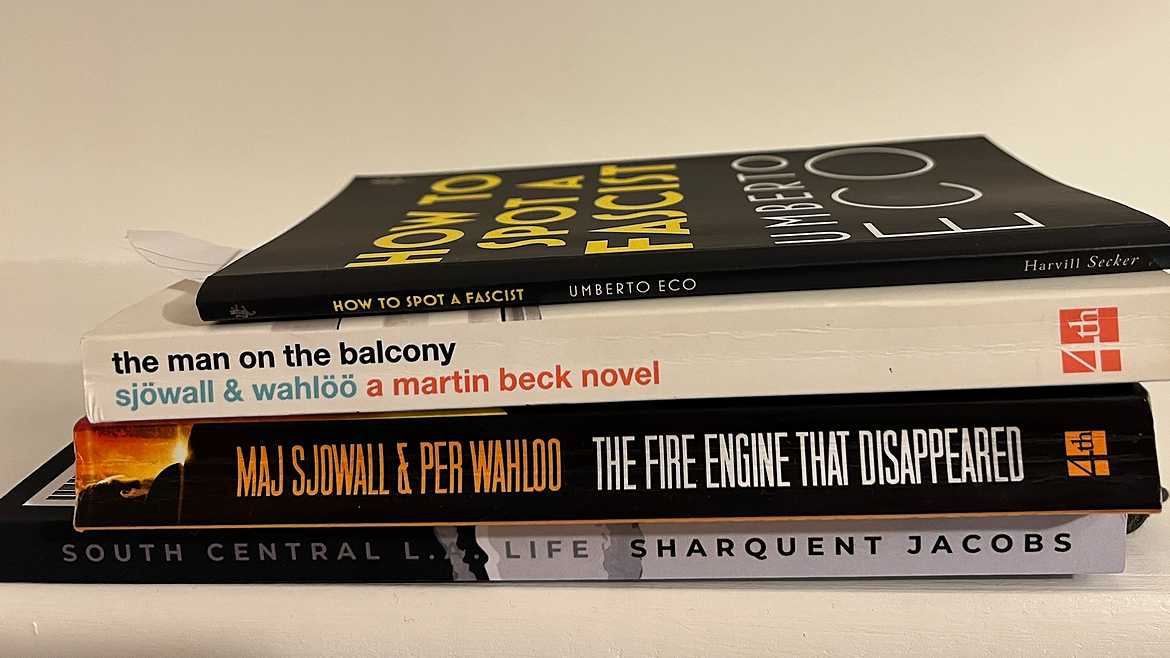

OCTOBER BOOKS 2023

Thin stack this month - but fat reading.

THE MAN ON THE BALCONY by Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, 4th Estate, Random House 1968/2007/2016

The Martin Beck series by Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo is authentic, propulsive and profound. Every novel is paced and plotted like a watch. The characterisation is exquisite yet only ever serves the forward motion of the narrative. The Man on the Balcony and The Fire Engine That Disappeared so far are my two favourites in the series, with The Man on the Balcony just topping Fire Engine. Both combine the utter despair of policing the unpoliceable and the comic grotesque truth of trying to establish law and order. The actual procedural work has none of the melodrama and panic of current police procedural; instead, it really does focus on the basics of policing: the mundanity of follow-up, observation, lateral thinking, pointless days, waiting, watching. The impossibility of family life when your head is constantly trying to relate to the evil forces that destroy families, live in families. You can tell both Sjowall and Wahloo were both journalists by trade as the work day and the narratology of a journalist and a police officer are almost identical. Sjowall and Wahloo point to the era of relative ‘innocence’ before the nationalisation of the police when they were pushed from being ambivalent protectors and detectives to being part of the whole capitalist/state/crime industry. It’s telling that all the titles of their novels read like Ladybird children’s books: The Abominable Man, The Fire Engine That Disappeared, The Man who went up in Smoke. Maybe not The Terrorists and Cop Killer…but still, these two writers are masters of the telegraphic procedural. It’s hard to find a better one. I always feel richer and wiser for having read one and it hasn’t put me off wanting to go to Scandinavia.

SOUTH CENTRAL L A LIFE by Sharquent Jacobs, Outskirts Press Publishing, 2021 *****

This is not crime fiction. It’s the actual memoirs of a most fast, furious and feral life lived on the streets of LA, wasted in every single sense of the word. Not only did Sharquent live this life, not only did she survive this life but she was literally given a new one for the old.

It is common (or at least Google) knowledge that I spent my twenties with rappers, gangsters, ex-cons, former pimps, prostitutes, con men and addicts in various shapes, sizes and disguises, writing down their stories, fears, dreams and instructions. However, I can honestly say not one of them have a life experience to rival Sharquent’s. In fact, she was always my barometer of craziness.

First , a disclaimer of bias: I know Sharquent. She was a great friend of mine in the early 1990’s. However, I did not know her as in I didn’t know her full story. If I hadn’t met Sharquent, a lot would not have happened. I’d always felt a strong identification with the lost ethnics since reading ‘The Cross and the Switchblade’ aged twelve and other testimonials my mum had on her bookshelf; I’d outgrown Barnsley Central Library in primary school. Prior to discovering The Strand bookshop in New York, my only other fantastic find was a recent release called Iced by Ray Shell in 1993 which I read in one weekend when living in London. It was the stream-of-consciousness diary of a crackhead in the throes of addiction. I was transfixed by the first person present tense prose more than by its contents. That in itself conveyed to me the state of timeless utter wretchedness and degradation, a non-stop hell of permanent desire and no satisfaction. Its pace and flow conveyed a prodigal waste of everything life is – a state of being conveyed so poetically I never forgot it. I’ve been a teetotaller all my life but that book told me everything I needed to know, if ever there was curiosity, about the experience. It is tragic that it’s out of print. I took my copy with me to California but gave it to my neighbour in Watts.

However, Sharquent’s book is something fiercer than even Shell’s work. I met her in the August of 1994 on the Holloway Road during one of the crusades and later went to stay with her in San Diego for a week or two before heading to South Central Los Angeles. We lost touch after that but I never forgot those days spent with her and her daughter, Saquena. When I later was a mentor and teacher at Peace4Kids in Watts, I always thought of them both.

When she messaged me on Instagram, I bought her book off Amazon and it automatically felt like part of a personal history. I knew some the places and people in it, recognised the scenarios as being similar to the ones the youth I looked after went through. Several years older than me, she was part of the true crack epidemic that hit South Central in the 1980s and her writing, unblunted by formal education, is raw, real and visceral. It’s so intense, often I had to put the book down and cry, scream or go for a long walk to vent. As a female survivor of the most horrific neglect, abuse, sexual predation, incest and the inevitable descent into full-blown addiction, violence and total depravity, she holds nothing back. There is zero vanity here. It is the real deal. She doesn’t even attempt to excuse her behaviour or convey regret or blame sociopolitics.

I didn’t recognise this child, this teenager, this woman on these pages – and yet I did. What was strangest, I identified so much with her. I was raging, in tears in many parts. I raged at her, loved her, shook my head at her, cheered for her, wept for her. When I knew her, she was a woman with so much love and energy…and that was after a life of such complete depravity and deprivation, she shouldn’t be alive yet alone sane.

Her story documents her heartbroken mother who, after her father left, had a breakdown and spent her years ‘dumpster diving’ for food and junk, turning their home into a rat and roach infested cesspit. I don’t think I’ve ever heard such a place described even in the worst horror stories. On top of this, the detailed revelations of the continuous predatory males, the sexual abuse, the incest, rape…all before she was even twelve. Women like Sharquent do not get to have their stories told – let alone to tell it in their own words. Sharquent has and does and it’s a fierce gut-wrenching tale. At times, I found it difficult to read; it was like a secondary trauma. I had to put it down as I just couldn’t process what I was reading. Having worked with foster youth in South Central, the offspring of addicts and negligent mothers and broken systems, I felt real anger at times and really sorry for her children, one of whom I knew personally. Yet by the end of the book, I too had more compassion. I also understood exactly what had drawn me to this woman back in London before my own nightmare journey started.

Our friendship was a very unlikely one in the strangest of times but it was nonetheless real and started with a prayer. At the time, I think we both believed we were as different as two women could be and yet, reading her memoirs, I humbly realise how similar we are.

For someone who has been on crack with the intensity and for that length of time, the fact that Sharquent can still remember, let alone articulate the experience is incredible. She does it down to the real nitty gritty details, from sleeping for days under an upturned paddling pool when in the crack come-down coma to delivering the most severe violence to another woman and the feelings afterwards, is a miracle. But it’s only one of many.

The best part for me was the last quarter of the novel but it’s the whole thing which left me feeling enriched and overwhelmed with joy. Not a shred of sentimentality in there. You can keep your cosy crime and fantasy sagas – they do nothing for me.