MY MUM'S MAKE-UP CASE

The Case for Vanity

SURVIVAL TOOLKIT FOR WOMEN

I recently splashed out on a vanity case. In fact, not just one. Four. One from Mango and two from Cult Beauty and then a massive one from Amazon. I have never, ever done this in my life before. It felt like the height of utter indulgence at a time when I should be most frugal. The overturning of Roe v Wade prompted it. My make-up and skincare routine is now a priority. It is more important than my clothes or heating. And it made me ask why? Why, in times of scarcity, struggle or hardship, do we reach for organising, make-up and skincare? And what can it mean when we stop?

My mum had an old Tupperware vanilla ice cream tub as her make-up box. It was kept strictly off limits, on the topshelf of the bathroom cabinet, mirror door closed. So, of course I was going to get in there. I wanted to find the magic that transformed my usually raw, puffy-aced, frowning mother into a glowing, dazzling film star with a big radiant smile, sparkling eyes, smelling of summer and happiness. I loved it when my mum wore make-up: ‘Let me see! Let me see!’ I’d unclick the lipstick just to smell that lipstick smell that reminded me of mum as pretty – not as mum the washerwoman/cook/nappy-changer.

The 1970s and 1980s in Yorkshire were the brutal years of the Ripper, inflation, strikes upon strikes and grim survival. Any sign of colour, joy or the exotic was seen as illicit, provocative, vulgar – not fitting in with the era of misery, doom and austerity. My mum didn’t have a clothing budget as she was a stay-at-home mum but she did have skills. She sewed exotic modern gowns using her pile of Indian sari fabrics from our friends who ran a textile factory in India and the 20 p Vogue patterns bought in Barnsley’s Woolworths or Butterfields. When my parents were invited out to dinner, she shone like a movie star. I can still hear the rustle of her long gowns, still have the ‘spare’ pearl buttons, swatches of sparkly fabric we got to use with our Sindy dolls.

There was nothing remotely frivolous or vain about this activity. Believe me, it achieved everything it set out to do: establish confidence in who she was, the family name and engineer opportunities for herself and her children. Her presentation was her CV – not just of herself but of her family. It was my mum’s aesthetics and social skills, not my dad’s chronic shyness and preference for a quiet room and Radio 4, that built critical social networks, activities, relationships. Our house was bought on the strength of mum’s personality (she had zero equity – but the estate agent owner’s wife loved my mum and wanted her to have it), the extension and planning permission was through her personality and charm, the garden’s cultivation. My parents were stalwart teetotallers – which did not bode well for a social life in Barnsley. But my mum’s ability to throw her personality into her appearance is what won hearts and minds. She could transform a room with her style.

However, not everyone liked this. The reaction of her biological twin sister was horror. She repeatedly told my mum that wearing lipstick and mascara was a sin, as was her pierced ears. Other women in strict Brethren circles told mum she was promiscuous for wearing make-up and that their husbands wouldn’t let them – as if it was a failing on my dad for allowing it. My dad not only allowed it; he encouraged it. When mum wanted earrings, he pierced her ears himself. He allowed her access to the most exotic fabrics because it channelled her creativity. He didn’t want her to be an anorak-wearing drab woman. Getting dressed up was not a sign of seduction; it was a sign of assertion.

Beauty, make-up and style is not vanity.

The acceptable version of British beauty was not my parents. In a time when fighting back was practically impossible politically, make-up and style was the one place you could defy conventions. It could be said that the reason British fashion, music and style has become so strong and internationally iconic is because it evolved in a classist, racist nation where the political and economical rights of so many were oppressed. America had more freedom – but it didn’t have more style.

My mum’s humble tub of Revlon blue, green and shimmery cream eyeshadows, pearly pink, matte magenta, rose-pink lipsticks, mascara and setting powder was her paint pot. It was her defiance against her jealous mean-spirited so-called sister and ‘friends’, friends who walked away from her during cancer. The gold earrings, pearls and new style jewellery were her crown jewels. She called it ‘looking smart’. Her friends called it ‘vanity’. But the true definition of vanity is something empty, worthless, of no substance or value. The fact that my mum taking care of herself was seen as ‘vanity’ says everything about society – and nothing about my mum.

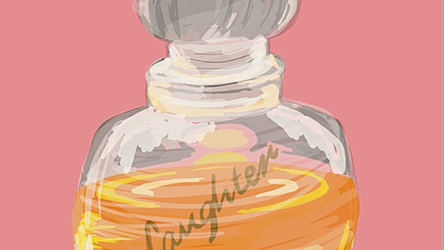

It wasn’t just the jewels and make-up, it was the perfume. When my dad returned from doctor conferences in Berne, Zurich or Munich, he would bring her trays of mini perfumes. But her signature scent was ‘Laughter’ by Yardley, a progression from ‘Lily of the Valley’ – just as her personality had evolved. I still have a small bottle of her eau de parfum. I ration it but all it takes is for me to open that stopper and, like a genie, she springs froth, fresh as a daisy, telling me: ‘What do you wish for, Nina? It's yours, it’s yours!’

But the jealousy and taunts did get to her. Her hourglass figure, her glossy thick hair and sparkling grey-hazel eyes, warm smile were a liability because they were too attractive. She ate for comfort instead of confronting the meanness or defying it. She stopped dressing up. When she did finally see a private friend-of-the-family gynaecologist, (she wouldn’t dare go to a GP or someone local), it was too late. She needed a hysterectomy – shortly followed by a mastectomy and then the other breast went. Stage 4 cancer moved in shortly after. She was not yet forty. The reason she wouldn’t persevere with chemo was because she didn’t want her hair to fall out.

Her only confidant and real helper during this time was Smutri, a trained dietitician and the Indian wife of a new GP in the area. Smutri was the only woman I saw my mum totally trust. It was my job to accompany mum to her radiotherapy and chemo, to visit her in between sitting my exams. She told me everything, my younger siblings nothing. They didn’t even know she was dying. I watched a woman in her prime wither – all because self-care was seen as obscene; dogma, others’ needs and opinons came first. I vowed it would never happen to me.

Funny, after my mum’s death, her twin started wearing full face make-up.

Vanity is working for a system or society that does not value you, does not invest in you, neglects you.

My own health journey is another story but I wondered why I reacted so viscerally when I heard that Rode v Wade had been overturned. I didn’t understand why every nerve and fibre in my body screamed. I’m not American, don’t live there, am not of child-bearing age yet, for me, this was the explicit oppression I, and my mother, had struggled against all our lives.

My mum was a gold medallist midwife before she had three children and lost her career; at the end of her life, she reflected bitterly on this. If you are a woman born without wealth or connection, you know the struggle. You know why healthcare is important, why real female friends, a support system is vital, why beauty, make-up and fashion is not vanity. You are worth something, you matter. You have value. What is vanity is working for a system or society that does not value you, does not invest in you, neglects you. That is vanity.

Make-up, skincare, healthcare, financial care, style is not vanity – it’s armour. It’s a war cry: it’s the first battalion. The first defences the enemy tries to knock down. But it’s not the last. If he can knock your confidence, he can get to everything else.

I’ve looked in the mirror, bare-faced, and seen the lines of pain, fear, loss, unbelievable sorrow and said: ‘I cannot bear to look at her ever again!’ I burst into tears, pushed the make-up away. And then I heard a voice. No – it wasn’t the mirror telling me I was the fairest of them all (because I’m not). It was a voice that does not need a mirror.

‘Nina, look at that face as if it is the face of someone I love, I cherish, I hold dear.’

I believed it to be the voice of God. God and make-up? God and women’s self-loathing? Yes. When I heard those words, I knew it was God because they were the words of love. They melted something inside me. My face hadn’t changed one bit , but when I looked in the mirror again, what I saw was someone who was cherished, treasured. And that changed everything.

Now I enjoy putting on my make-up because I am putting it on a face that is loved. Not was loved but is loved. I relish putting my health first because it reminds me I am loved. It’s changed how I see my female friends – both when they are winning or when they are going through challenging times. Suddenly, I know what they need. I know how to remind them they are loved, they are special, they are precious. They are not competitors; their success is my success too. They are fellow soldiers I am inspired by or I can help.

My mum's tub of make-up still inspires me; it is a source of profound mystery and symbolism of the essence of my mother during the worst of times. To watch her put on her make-up was both an act of love and a seizing of power. It was the equivalent of a Declaration of Intent. For a seven year old, the smell of the lipstick was the smell of that power.