AUGUST BOOKS 2023

Structural edits month for final draft so not much time for reading. Plus being blind in one eye slows me down! But these are the gems that have made a big difference this month...all fuel to current works in progress.

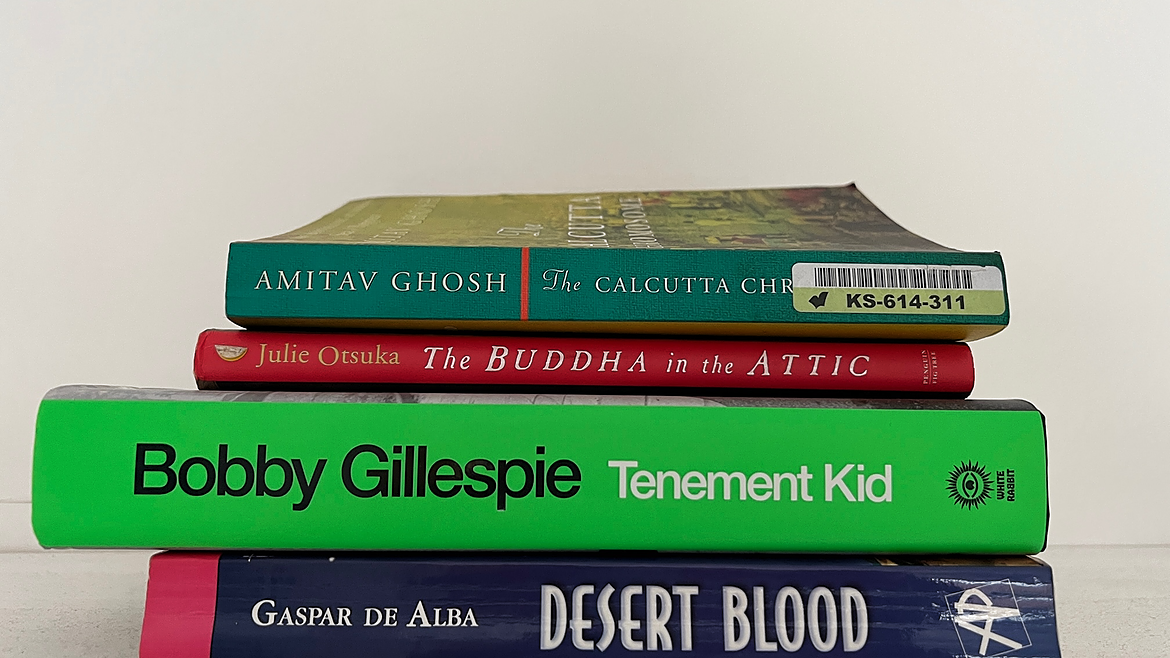

'Desert Blood' by Gaspar de Alba - Arte Publico Press, 2004

There have been many books written based on The Juarez murders – the brutal violence, kidnapping and femicide of hundreds of young Mexican women by an anonymous syndicate made up of border officials, maquiladora owners, businessmen and voyeurs that occurred in Ciudad Juarez in 1998-2005.

Due to the lack of a proper criminal investigation and the failings – or rather criminally complicit judicial and political system – too much forensic evidence was lost and the true number of crimes and identification of victims is largely limited to the work of various NGOs and activist groups. The women were chosen because they were seen as marginalised, with no power except in their fecundity. This makes the story of the crimes, spread over so many years and jurisdictions, particularly difficult as many of the mispers were either never properly reported, recorded, or found. Various crime fiction narratives have been built around the myths, facts and legends surrounding the horror including: Sam Hawken’s ‘The Dead Women of Juarez’ (Serpent Tail 2011) and Teresa Rodriguez’ ‘The Daughters of Juarez – A True Story of Serial Murder South of the Border’ (Atria Books, 2007). However, de Alba’s novel ‘Desert Blood’ (Arte Publico Press, 2005) suggests the movement of rage against the social political systems that created the problem and allowed it to continue. In this, it is both ambitious and points to the challenges of articulating transnational crime.

To start with, de Alba’s protagonist Ivon is, like herself, a lesbian professor living in Los Angeles, trying to complete a paper on Latin American sociopolitics – trying to adopt a Mexican child with her lover, Birgit. Returning to her hometown El Paso, Ivon is confronted with some ugly realities that are beyond her academic understanding. The pregnant mother of the child is found brutally savaged in the desert, her own 16 year old sister, Irene, is kidnapped and there’s a conspiracy of silence about the slew of femicides that are happening. Ivon abandons her rigid academics which falter at such complex corruption. Instead, she goes into the field, opening up terrifying doors that lead her to unravelling a cross-border conspiracy involving police, Border patrol, the INS and the corrupt judiciales.

While the plotting is clunky and it is difficult to se the purpose of dramatic irony regarding the intelligent, aware Ivon’s inability to join the dots when the reader has them explicitly painted, the textural detail, dialogue and focus on the victim’s experience makes this a more compelling read to the other Juarez’ novels.

Alba uses a range of texts, court reports, bilingual vernacular, autopsies, flyers, newspaper write-ups, contemporary song lyrics all mashed up with academese and a pulp-fiction, graphic style. It reads like a real experience, blunt and true, sensationalising nothing and placing the reader firmly in situ. The novel is, without doubt, the most graphically disturbing one I have ever read – underlined by the knowledge it is based on truth. But it also demonstrates the culture of intense verbal and physical violence against women which is endemic to both Mexican and American society. By giving the victims names, lives, histories and personalities, while the perpetrators remain blurry masks of horror or nameless, she shows the hopeless task of prosecution while redeeming the victims’ rights to have the horror of what they endured acknowledged.

The effort to wrap-up a story that has no wrapping-up could have been omitted to greater effect. It is brutal, harsh but also vital. It’s a novel about resilience and the declaration of an uncomfortable truth prescient of the world to come – the ‘silent’ partners in transnational crimes – and the challenges of writing crime fiction in the twenty first century when the judicial, border forces and employers are the ones writing the mainstream narrative. As de Alba states: ‘This wasn’t a case of “whodunnit” but rather of who was allowing these crimes to happen? Whose interests were being served? Who was covering it up? Who was profiting from the deaths of all these women?’ (p333) and ‘A bilateral assembly line of perpetrators, from the actual agents of the crime to the law enforcement agents on both sides of the border to the agents that made binational immigration policy and trade agreements.’

This is a novel well worth reading, not because it is technically well-accomplished but because it dares to try to articulate the realities of transnational crimes and thus reveal the areas of silence and deceit which need further penetration.

‘The Calcutta Chromosome’ by Amitav Ghosh - Avon Books, 1995

Ghosh is at once an Indian’s India – in that he was born in Calcutta and grew up in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and India – and diasporic as he’s also lived in England and the United States. This novels is a crime/mystery novel centring around a missing person, Murugan, an AI search engine and the history of malaria. It’s prototypically Indian in its convolutions and its relentless weaving of the rational with the irrational. It dips and dives between centuries and places yet somehow maintains a clear narrative link and deepening connection with its core of characters through a robust conversational style that sweeps the reader down a very dark, winding corridor that ultimately opens up into blinding light.

Although it focuses on the medical history of malaria through a conspiracy preventing its scientific investigation, it illustrates better the depths and layers of the continent’s subconscious as it resists colonialisation through an active silence. This is a novel that sings into your dreams, articulating thoughts you didn’t even know you silenced, and awakens an awareness of connections, a new way of thinking, without you knowing how. Bizarre and brilliant.

‘Tenement Kid’ by Bobby Gillespie - White Rabbit, 2021

I’ve no idea how Bobby Gillespie retained all this wonderful detail of the emergence of the only rock ‘n’ roll I’ve known. This is an encyclopaedic chronology of his journey from the maggoty garrets of Glasgow in the mid 1970’s through to the creative butterfly of Primal Scream. It includes all the lesser-known influences that didn’t make the album sleeve notes, the anecdotes and reflections. It’s not a narcissistic memoir really – more of an A to Z, a rock ‘n’ roll encyclopaedia on steroids and acid, immersing you into a world of such varied, rich connections where the cosmic soundscape and hard edges of Primal Scream were birthed and formed. It’s a book where I constantly needed a reference sheet or Google for every page and it left me feeling both humbled and hopeful. If you’ve ever been to a Primal Scream gig, you’ll know what I mean. Pure working class joy. Real class.